Chapter 7

The Date of Devakīputra Vāsudeva Krishna and

Krishna of the Mahābhārata Era

The evolution of ancient Indian calendric Yuga system – from the five-year Yuga and the twenty-year Chaturyuga of Vedic and post-Vedic era, to the Chaturyuga of 4320000 years of the post-Rāmāyaṇa era – had posed a great challenge to the Sūtas (Puranic updaters) of the post-Mahābhārata era. Unfortunately, the original texts of Purāṇas of the pre-Mahābhārata era and Purāṇas compiled by Vyāsa of the Mahābhārata era are not extant today. Seemingly, the available texts of Purāṇas and Itihasa (the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata, the Yogavāsiṣṭha and more) have been recompiled from the Maurya period to the post-Gupta period. The main objective of the periodic recompilation was to document more and more ancient Upākhyānas (historical legends) and mythological narratives of Devas, and also to update the genealogical chronology of various kings. The Puranic ślokas related to Upākhyānas were periodic additions to the original Purāṇa texts compiled by Vyāsa, whereas the ślokas related to the genealogies had been periodically updated.

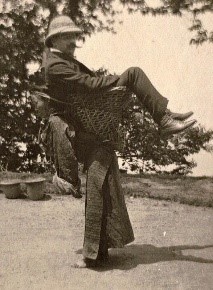

It appears that Itihasa texts like the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata were also recompiled during the Maurya and the post-Maurya eras. The popularity of Adhbuta Rasa led to the evolution of the mythological narrative of Itihasa. Since, the ancient Sanskrit words “Kapi”, “Garuḍa” and “Rikśa” became synonymous to monkey, vulture and bear respectively in Laukika Sanskrit, Sanskrit poets started imagining them as monkeys, vultures and bears to induce “Adbhuta Rasa”. Interestingly, the vāhanas of Devatas (deities) like Mūṣaka, Vyāghra, Simha, Mayūra, Nandi, Garuda, Śunaka, Haṁsa, Makara, Śuka, Ulūka, were actually human beings who were either the Sārathis of the chariots of Devatas or carried Devatas on their back. Gradually, these ancient Sanskrit names became synonymous with names of animal and bird species in Laukika Sanskrit. Travelling on the back of a strong man was practiced even during the Colonial era in India. The following photograph of a British merchant being carried by a lady on her back in Bengal has been taken in 1903.

The concept of the Chirajīvīs in the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata and Purāṇas, and the concept of twenty-eight Vyāsas evolved due to the confusions in the chronology of events in ancient times. According to Puranic legends, Aśvatthāmā, Bāli, Vyāsa, Hanuman, Vibhīṣaṇa, Kripāchārya, Paraśurāma and Rishi Mārkanḍeya were the eight long-life personalities (अश्वत्थामा बलिर्व्यासो हनुमांश्च विभीषण: कृपश्च परशुरामश्च सप्तैते चिरजीविन:। सप्तैतान् संस्मरेन्नित्यं मार्कण्डेयमथाष्टमम्।). Saptarṣis, Jāmbavān, Devāpi, Maru, Muchukunda, Bāṇāsura and Kāka Bhuśunḍī, among others, were also considered to be Chirajīvīs. We will discuss the dates of these Chirajīvīs later.

Evidently, there were numerous chronological challenges in explaining the historical legends of ancient India. Consequently, the updaters of Itihasa texts and Purāṇas had committed certain mistakes in the presentation of genealogical and chronological history. One such chronological mistake is the dating of Devakīputra Vāsudea Krishna. They erroneously assumed Devakīputra Krishna and Krishna of the Mahābhārata era to be identical, which led to the following chronological inconsistencies. I have conclusively established that Devakīputra Krishna lived in the Rigvedic era, around 11150-11050 BCE, whereas Krishna of the Mahābhārata era lived around 3223-3126 BCE. Let us discuss these chronological inconsistencies.

- Cḥāndogyopaniṣad mentions that Devakīputra Krishna was a pupil of Rishi Ghora Āṅgirasa who wrote a Sūkta of Rigveda in Vedic Sanskrit. Evidently, Ghora Āṅgirasa and Devakīputra Krishna lived before the evolution of Post-Vedic Sanskrit and Laukika Sanskrit. Sri Krishna of the Mahābhārata era was the pupil of Muni Sāndipani. Cḥāndogyopaniṣad narrates: “तद्धैतद्घोर आङ्गिरसः कृष्णाय देवकीपुत्रायोक्त्वोवाचापिपास एव स बभूव सोऽन्तवेलायामेतत्त्रयं प्रतिपद्येताक्षितमस्यच्युतमसि प्राणस शितमसीति तत्रैते द्वे ऋचौ भवतः” [Rishi Ghora Āṅgirasa imparted this teaching to Krishna, the son of Devakī and it quenched Krishna’s thirst for any other knowledge and said: "When a man approaches death he should take refuge in these three thoughts: ‘You are indestructible (akśata),’ ‘You are unchanging (aprachyuta),’ and ‘You are the subtle prāṇa.’ With regard to that there are two Rik-mantras.”].1

Rishi Ghora Āṅgirasa was the author of one mantra of Rigveda.

अस्मे प्र यन्धि मघवन्नृजीषिन्निन्द्र रायो विश्ववारस्य भूरेः ।

This mantra is written in Cḥāndas or Vedic Sanskrit. Therefore, Ghora Āṅgirasa and his pupil Devakīputra Krishna lived in the Rigvedic era and not in the Mahābhārata era.

अस्मे शतं शरदो जीवसे धा अस्मे वीराञ्छश्वत इन्द्र शिप्रिन् ॥ - The legend of Kāliya Mardana informs us that Krishna was the contemporary of Kāliya Nāga. Kāliya was a descendant of the Nāga lineage of Kadru and Rishi Kaśyapa. The Garuḍas were the descendants of Vinatā and Rishi Kaśyapa Prajāpati. Admittedly, neither the Garuḍas were vultures nor the Nāgas were serpents. They were cousin brothers. The Garuḍas were always in conflict with the Nāgas. Kāliya Nāga was forced to leave his ancestral place Ramanaka dvīpa (probably, a place between Yamuna and Charmaṇvatī Rivers) and took shelter in a place near Kālindī Hrada to avoid conflict with the Garuḍas. Rishi Saubhari was also residing near Kālindī Hrada. He warned Garuḍa not to enter Kālindī Hrada. Evidently, Kāliya Nāga and Garuḍa were contemporary of Rishi Saubhari who married fifty daughters of the Ikśvāku King Māndhātā (11150 BCE). Since Kāliya Nāga started harassing the people of Kālindī Hrada, Krishna taught him a lesson and asked him to leave Kālindī Hrada and go back to Ramanaka dvīpa. The Puranic updaters mythologized the legend by assuming Kāliya Nāga as a venomous serpent. Chronologically, Devakīputra Krishna and Kāliya Nāga lived during the lifetime of Rishi Saubhari.

- According to Garga Saṁhitā and Brahma Vaivarta Purāṇa, Pūtanā was a daughter of Rakśasa King Bali, son of Virochana. Vāmana forced King Bali to hand over his kingdom to Devas. Probably, the Asuras became generals of King Kamsa. Pūtanā tried to kill Krishna in his childhood. Aghāsura, Bakāsura and Triṇavrata were the brothers of Pūtanā. Śakaṭāsura, a contemporary of Krishna was a descendant of Utkacha, son of Hiraṇyākśa. Baladeva or Balabhadra, the elder brother of Krishna, killed an Asura named Pralamba. Evidently, Asura King Bali’s sons and daughters were contemporaries of Krishna. King Bali lived before the Rāmāyaṇa era. Since Purāṇa updaters mistakenly assumed Devakīputra Krishna to be a contemporary of the Mahābhārata era, they had no other option but to accept that King Bali was a Chirajīvī and lived up to the Mahābhārata era. In fact, there were no Asuras or Rakśasas during the Mahābhārata era.

- Narakāsura, a contemporary of Devakīputra Krishna, was a descendant of Hiraṇyākśa. The Rāmāyaṇa refers to the legend of Narakāsura who was killed by Vishnu or Krishna. Therefore, Devakīputra Krishna lived before the Rāmāyaṇa era.

- Dvivīḍa of the Kapi community was a friend of Narakāsura. Dvivīḍa started harassing the people of Ānarta kingdom to avenge the death of Narakāsura. He might have attempted to kidnap Krishna. Finally, Baladeva killed Dvivīḍa. Interestingly, Dvivīḍa and his twin brother Mainda helped Sri Rāma during his war against Rāvaṇa.

- According to Harivaṁśa Purāṇa, Kālayavana was the son of Rishi Gārgya’s Śyāla (brother-in-law) and Apsaras Gopāli. Kālayavana became the King of Yavanas and attacked Mathura. Krishna left Mathura and proceeded towards Dwārakā. Following Vāsudeva Krishna, Kālayavana entered a cave in Raivataka Hills (Girnar) and got killed by Muchukunda. This legend of Kālayavana clearly indicates that Devakīputra Krishna was a contemporary of Muchukunda, son of King Māndhātā (11150 BCE). Confused, Purāṇa updaters mistakenly started believing that Muchukunda was a Chirajīvī.

- The legend of Ikśvāku King Nriga informs us that Krishna was also a contemporary of King Nriga. Interestingly, Sri Rāma relates the story of ancient Ikśvāku King Nriga to Lakśmaṇa in Uttara Kānda of the Rāmāyaṇa. Sri Rāma also refers to Vāsudeva Krishna. The Mahābhārata also relates the story of Devakīputra Krishna and King Nriga (अथैनाम् अब्रवीद् असौ ननु देवकीपुत्रेणापि कृष्णेन नरके मज्जमानॊ राजर्षिर् नृगस्तस्मात् कृच्छ्रात् समुद्धृत्य पुनः स्वर्गं प्रतिपादितेति). There was no Ikśvāku king named Nriga during the Mahābhārata era. In fact, King Nriga was a contemporary of King Māndhātā. It is evident that Devakīputra Krishna flourished before the Rāmāyaṇa era.

- Devakīputra Krishna married Satyabhāmā, daughter of King Satrajit. The legend of Śyāmantaka Maṇi tells us that Jāmbavān killed Prasena, brother of Satrajit and had stolen Śyāmantaka Maṇi. Krishna defeated Jāmbavān and married his daughter, Jāmbavatī. This Jāmbavān was the ancestor of the Jāmbavān of the Rāmāyaṇa era. Yāska’s Nirukta refers to Akrūra and Śyāmantaka Maṇi. The Mahābhārata refers to Yāska. Evidently, Yāska wrote Nirukta before the Mahābhārata era. Aitareya and Śatapatha Brāhmaṇas also refer to King Satrajit and his son Śatānīka. Yājñavalkya and Mahīdāsa Aitareya lived during the era of Post-Vedic Sanskrit and before the Rāmāyaṇa era.

- The historical story of Pārijātaharaṇa as narrated in the Mahābhārata, Harivaṁśa Purāṇa, Bharatamañjarī of Kśemendra, Harivijaya of Sarvasena relate that Krishna forcibly removed the Pārijāta tree from Amarāvatī, the capital of Indra and took it to Dwārakā after subjugating Indra and planted it in the courtyard of Satyabhāmā. There was no Indra during the Mahābhārata era.

- Dravida, son of Krishna and Jāmbavatī, was the progenitor of Dravidas. The Dravida kings were already established in Tamil Nadu before the Mahābhārata era. Sahadeva subjugated Dravidas during the Rājasūya Yajña of Yudhiṣṭhira. The Dravida kings supported Pāndavas in the Mahābhārata War.

- Pradyumna was the son of Krishna and Rukmiṇī. Once Asura Śambara abducted Pradyumna. Asura King Śambara and his descendants lived in the Rigvedic period. The Rāmāyaṇa mentions that Indra killed Śambara. There was no asura named Śambara during the Mahābhārata era.

- Krishna and Pradyumna fought against Rākśasa Nikumbha and killed him. Nikumbha was a descendant of Hiraṇyakaśipu. Sunda and Upasunda were the sons of Nikumbha. The Rāmāyaṇa refers to Sunda and Upasunda. Evidently, Pradyumna flourished in the Rigvedic period.

- Aniruddha was the son of Pradyumna. He married Uṣā, daughter of Bāṇāsura and granddaughter of King Bali. Evidently, Aniruddha lived in the Rigvedic period.

- The legend of Kakudmi and Baladeva indicates that Revatī, a daughter of Kakudmi, reincarnated as Jyotiṣmatī after twenty-seven Yugas and married Balarāma. It seems Revatī was married to Baladeva, the elder brother of Devakīputra Krishna, in the beginning of Vaivasvata Manvantara, whereas Jyotiṣmatī was married to Balarāma II, the brother of Krishna of the Mahābhārata era.

- Rishi Śaradvān was a great grandson of Rishi Gautama and Ahalya. He was a contemporary of King Pratīpa and his son Śāntanu. His son was Kripāchārya and daughter was Kripī who married Droṇa. Aśvatthāmā was the son of Droṇa and Kripī. Since Kripāchārya and Aśvatthāmā lived in the beginning of Vaivasvata Manvantara, they were also considered to be Chirajīvīs.

- Megasthanese refers to Śūrasena, the land of two cities, namely Methora (Mathura) and Kleisobora (Kalpapura or Kalpipura). He considers Indian Krishna and Greek Heracles to be identical. He mentions that Indian Heracles lived 6042 years before Alexander. Evidently, Megasthanes refers to Devakīputra Krishna of the pre-Rāmāyaṇa era.

- Interestingly, Rishi Vasiṣṭha relates the story of Devakīputra Krishna to Ikśvāku king Dilīpa, an ancestor of Sri Rāma as recorded in Padma Purāṇa.

- Nammalvar, the fifth Tamil Vaishnava saint, (born in 3173-3172 BCE) and Ānḍāl (born in 3075 BCE) wrote poems dedicated to Lord Sri Krishna. Ānḍāl composed two poems in which she expressed her love for Sri Krishna. She imagined herself as Gopī of Sri Krishna. Evidently, Lord Sri Krishna was well established as Vishnu’s incarnation before the Mahābhārata era. There are numerous references of Krishna as incarnation of Vishnu in the Mahābhārata. Udyoga Parva refers to Krishna as Nārāyaṇa.

एष नारायणः कृष्णः फल्गुनस्तु नरः स्मृतः नारायणॊ नरश्चैव सत्त्वम् एकं द्विधाकृतम् ॥

Seemingly, Nārāyaṇa was another name of Devakīputra Krishna. Rishi Nārāyaṇa, the author of Puruṣa Sūkta of Rigveda, was none other than Vāsudeva Krishna. Phalguna was the name of Arjuna of the Rigvedic era. Therefore, Mahābhārata refers to Phalguna as Nara.

एतौ हि कर्मणा लॊकान् अश्नुवाते ऽक्षयान् ध्रुवान् तत्र तत्रैव जायेते युद्धकाले पुनः पुनः ॥

तस्मात् कर्मैव कर्तव्यम इति हॊवाच नारदः एतद्धि सर्वम् आचष्ट वृष्णिचक्रस्य वेदवित् ॥

शङ्खचक्रगदाहस्तं यदा द्रक्ष्यसि केशवम् । - Mahānārāyaṇopaniṣad was written in Post-Vedic Sanskrit before the Rāmāyaṇa era. It refers to Vāsudeva, Nārāyaṇa and Vishnu.

- According to the Mahābhārata, Yudhiṣṭhira requests Bhishma to narrate the ancient legend of Śukācharya. If Śuka was the son of Vyāsa of the Mahābhārata era, how had Bhishma eulogized Śukāchārya of ancient times?

- A dialogue between Śuka and Rāvaṇa has been related in the Yuddha Kānda of Adhyātma Rāmāyaṇa. How can Śuka of the Mahābhārata era be a contemporary of Rāvaṇa?

- The seventh Sarga of Adbhuta Rāmāyaṇa relates the story of Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu. Undoubtedly, Adbhuta Rāmāyaṇa indicates that Krishna had flourished before the Rāmāyaṇa era.

- While answering to a question of Rishi Vasiṣṭha, Rishi Viśvāmitra says that Sri Rāma is indeed an incarnation of Vāsudeva as recorded in Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Evidently, Vāsudeva Krishna must be dated before the Rāmāyaṇa era.

- Jain Āchārya Hemachandra indicates that the incarnation of Vishnu as Krishna was before than that of Rama.

- Kalpasūtra of Bhadrabāhu refers to Chakravartins, Baladevas and Vāsudevas. Later Jain texts indicate that Rāma was one of Baladevas.

- Jain version of the Mahābhārata describes the story of Kauravas and Pāndavas and the descendants of Krishna and Balarāma. Interestingly, Jain Mahābhārata indicates that Krishna fought against Jarāsandha. Seemingly, Jarāsandha invaded Mathura at least twenty years before the Mahābhārata War. He had the support of Kashmir king Gonanda I.

- Guru Govind Singh gives the list of twenty-four Avatars. According to him, Balarāma was the eleventh Avatar, Rāma was the twentieth and Krishna was the twenty-first. How can Balarāma be placed nine Avatars before Rāma? Seemingly, Balarāma and Krishna were incarnated before the Rāmāyaṇa era.

- There was an ancient city which was built on the two islands in the Gulf of Khambat. The fortress found is situated 131 ft (40m) below the current sea level.

- The Southern Metropolis (the first Dwārakā) was dated at the end of the Second Ice Age, around 11000 BCE.

- Sh. Badrinarayan of NIOT found that a couple of palaeochannels of old rivers were discovered in the middle of the Cambay area, under 20-40m underwater, at a distance of about 20 km from the present day coast: One over a length of 9.2 km and the other 9 km. Evidently, the southern palaeochannel was indeed Mahānadī, as recorded in Harivaṁśa, flowing through the city of Dvāravatī.

- To the south of this township, in the Gulf of Cambay, side scan sonar picked up a drowned dead coral colony 400m long, about 200m wide, and at 40m deep under water, substantiated later by sampling. It is a well-known fact that these corals live in hardly 2 to 3m water depth, very near coastal areas. They require a clean environment and good sunlight. Obviously, the southern metropolis appears to have been near a sea coast at a particular point of time, when the metropolis itself stood on dry land with a good free-flowing river, and was a major bustling city.

- It is seen that these features are 5x4m size on the eastern side, whereas the westernmost part had dimensions of 16x15m. The habitation sites are all seen to be laid in a tight grid-like pattern indicating a good sense of town planning by Viśvakarmā.

- There is a rectangular (41mx25m) shaped depression wherein one can see steps gradually going down to reach a depth of about 7m. Surrounding this depression there is a wall-like projection on all sides. This looks like a tank or bathing facility under 40m of sea water.

- A black alluvium that somewhat semi-consolidated and collected above the river conglomerate gave an age of 19000 BP. Obviously the river has been flowing at least between 19000 years BP, prior to Glacial Maxima, and up to 3000 BP. This shows that the palaeochannel in the north was active and a riverine regime existed at least from about 19000 BP.

- In the southern township or palaeochannel area, six samples suitable for dating were identified. Of these three are carbonized wooden samples; one was a sediment sample, one a fired pottery piece and one hearth material. Sample from the same carbonized wood was sent to National Geophysical Research Institute, Hyderabad, India and Geowissenschaftlicte Gemeinschaftsaulguben, Hannover, Germany for carbon dating. This was the first sample (Location 21o 03.08’ N; 72 o30.83 E) from near the southern palaeochannel. This first gave a clue to the age and environment of the civilization. The calibrated age as per NGRI was 9580-9190 BP and as per Hannover Institute it was 9545-9490 BP. It means the age is about 9500 BP, or 7500 BCE.

- One of the pottery piece found in this sunken city gave a date of 13000 ± 1950 BP. It is an important date. Another pottery piece that was kiln-fired, on OSL dating (Location 21 o12.54’ N; 72 o 30.370’ E) by Oxford University gave an age of 16840 ± 2620 BP.

- Three kiln-fired pottery pieces in the northern palaeochannel gave ages of 7506 ± 785 BP, 6097 ± 611 BP (both by Manipur University) and 4330 ± 1330 BP according to Oxford University.

- The sun-dried pottery pieces were also collected. Three of the specimens were dated by OSL facility in Oxford. The results obtained are: (1) 31270 ± 2050 BP, (2) 25700 ± 2790 BP and (3) 24590 ± 2390 BP. A black slipped dish that was also sun-dried was dated in Oxford by OSL to be the age of 26710 ± 1950 BP.

- The hearth material from the southern township (Location 21o03.04 N 72o30.70 E) by TL dating from PRL, Ahmedabad gave an age of 10000 ± 1500 BP, whereas the hearth material near the top in the northern township gave an age of 3530 ± 330 BP by OSL method, Oxford University. One of the charcoal pieces obtained on the northern side was tested by 14C dating in BSIP, Lucknow. It gave a calibrated age of 3000 BP. It tallies very well with the age of upper most alluvium in northern palaeochannel.

- The ancients were making potteries and were initially drying them in the sun. It is clear that the ancients have been firing clay to produce pottery for about 20000 years. That means they knew how to make, maintain and manage fire. They appear to have succeeded in making fired pottery from about 16800 BP.

- The strong evidence, i.e. the carbon dating of potteries, supports the presence of humans in the Gulf of Khambat from at least 31000 BP.

- Jaimini relates the story of Aśvamedha to Janamejaya, son of Vishnurāta. We have no information of Vishnurāta of the Mahābhārata era. Bhāgavata Purāṇa refers to Brahmarāta, a contemporary of King Vishnurāta.18 Seemingly, the names of Brahmarāta, Vishnurāta, Devarāta and so on belonged to Vedic era. According to Vishnu Purāṇa, Yājñavalkya, son of Brahmarāta, was one of the twenty-seven disciples of Vyāsa. Yājñavalkya I was the son of Devarāta and the disciple of Uddālaka I. Yājñavalkya II was the son of Brahmarāta. It may be noted that there were many Vyāsas from the Rigvedic era to the Mahābhārata era. Yājñavalkya II was the contemporary of King Janaka Vaideha (10870-10830 BCE). Thus, Brahmarāta and Vishnurāta can be dated around 10900 BCE. Since the story of Jaimini Aśvamedha and the story of the Mahābhārata got mixed up during the Gupta era, it was speculated that King Parīkśit of the Mahābhārata era came to be known as Vishnurāta because Sri Krishna (in form of Vishnu) might have saved Parīkśit in the womb of his mother Uttarā when Aśvathāmā used Brahmāstra on him.

- According to Jaiminīya Aśvamedha, Vyāsa suggests King Dharmarāja (also referred to as Dharmātmaja, Dharmaputra and Dharmanandana) perform Aśvamedha, and Bhimasena also encourages him. The suitable horse for Aśvamedha was available only with King Yauvanāśva. The Ikśvāku king Māndhātā was known as Yauvanāśva because he was the son of Yuvanāśva. Bhima, Vriṣadhvaja (son of Karṇa) and Meghavarṇa (son of Ghaṭotkacha) volunteer to bring the horse from the kingdom of Yauvanāśva. Sri Krishna discourages Dharmarāja and says that the Aśvamedha is not possible. But Bhima, Vriṣadhvaja and Meghavarṇa go to the city of Bhadrāvatī (Bhadresar of Gujarat) of Yauvanāśva and steal the horse. Furious, Yauvanāśva declares war with Dharmarāja but Dharmarāja and Bhima defeat him. Thereafter, Sri Krishna, Arjuna (Phalguna), Bhima, Vriṣadhvaja and Meghavarṇa lead the army and follow the Aśvamedha horse. Anuśālva, brother of Śālva, captures the horse but faces defeat. Pravīra, King of Māhiṣmatī and son of Nīladhvaja, also captures the horse but accepts defeat. King Nīladhvaja sends his son-in-law Agni to fight against Arjuna and Agni fails to defeat Arjuna. Jwālā was the wife of Nīladhvaja and Svāhā was the daughter of Nīladhvaja and Jwālā. Jwālā had a grudge against Arjuna because he defeated her son-in-law Agni. She requests his brother Unmukta, King of Kāshi, but Unmukta refuses to challenge Arjuna. Gangā, provoked by Jwālā, curses Arjuna that he will be killed by his own son within six months because Arjuna had killed her son Bhishma.

The Aśvamedha horse proceeds and gets stuck to a rock near the Ashrama of Rishi Saubhari. Arjuna is told by Rishi Saubhari that this rock is actually Chanḍī, cursed by her husband Uddālaka I. Arjuna liberates Chanḍī and restores her natural form. Thereafter, Haṁsadhvaja, King of Champāpuri, captures the horse. His fifth son, Sudhanvā, defeats Vriṣadhvaja, Pradyumna, Kritavarma, Anuśālva, Sātyaki and Nīladhvaja but gets killed by Arjuna. Haṁsadhvaja’s other son, Suratha, is also killed by Arjuna.

The horse reaches Gaurivana (Sundervan?) and proceeds to Nāripura (Naripur of Rangpur division, Bangladesh?). Queen Pramilā of Nāripura captures the horse. Arjuna marries Pramilā and, thereafter, the horse arrives in Rakkasapura of Burma. King Bhiṣaṇa, son of Baka, challenges Arjuna but gets killed. Finally, the horse reaches Maṇipura (Manipur). Babhruvāhana, son of Chitrāṅgadā and Arjuna, mistakenly captures the horse. He had no other option to fight with Vriṣadhvaja and his father Arjuna. Probably, Arjuna and Vriṣadhvaja get injured and fall into coma during the battle against Babhruvāhana. Ulūpi, daughter of a Nāga king named Kauravya, and a wife of Arjuna was also living with Chitrāṅgadā. Ulūpi played a major role in the upbringing of Babhruvāhana. She sends Puṅḍarīka to Pātāla (a Nāga kingdom on the banks of Ganga in Bangladesh) to bring Mritasañjīvikā from her father but Puṅḍarīka fails in his mission. Babhruvāhana invades and conquers the Nāgas and gets Mritasañjīvikā. The Nāga king Dhritarāṣṭra’s son, Durbuddhi, goes to Maṇipura and tries to cut off Arjuna’s head. Sri Krishna saves Arjuna and revives him and Vriṣadhvaja from Mritasañjīvikā brought by Babhruvāhana.

Babhruvāhana joins Arjuna for further course of Aśvamedha. Seemingly, the horse turns back from Maṇipura and reaches Himachal Pradesh in the North. Mayūradhvaja, King of Nāgari (Naggar city of Himachal Pradesh near Kullu), starts performing Aśvamedha and captures the horse. His son Tāmradhvaja (also known as Suchitra) fights with Arjuna and Sri Krishna. Finally, Mayūradhvaja abandons Aśvamedha and accepts defeat. Mayūradhvaja coronates his son Tāmradhvaja in the city of Tāmbravatī. Recently, some ancient copper mines have been discovered in Chamba district. There is a Tāmbravatī Mahādeva Temple in the city of Mandi. Most probably, the city of Tāmbravatī was situated in Chamba district.

The Aśvamedha horse now proceeds to the kingdom of Sārasvata King Viravarmaka. Probably, the kingdom of Viravarmaka was located in Rajasthan. Kāla married Mālini, daughter of Viravarmaka. Viravarmaka captures the horse but accepts his defeat. Thereafter, the horse proceeds to Kuntala kingdom (North Karnataka) of King Chandrahāsa who was an abandoned child of the King of Kerala. Chandrahāsa’s sons capture the horse but Chandrahāsa accepts defeat. The horse reaches the ocean. Arjuna meets Rishi Baka Dālbhya. According to Tamil legends, Arjuna marries the queen of Pāndya Kingdom.

Thereafter, the horse arrives in Sindh. Duśśalā requests Sri Krishna to revive Suratha who was in coma. Sri Krishna revives Suratha. Finally, Sri Krishna and Arjuna reach Hastinapura and narrate their victories over various kingdoms to Dharmarāja. Dharmarāja of Hastinapura now prepares to perform final rituals of Aśvamedha. Vyāsa suggests that sixty-four men should go to Ganga accompanied by their wives to fetch water for Aśvamedha. Sri Krishna was accompanied by Rukmiṇī, Satyabhāmā and Jāmbavatī. Finally, Dharmarāja’s Aśvamedha concludes successfully. However, a few days later, one Nakula (a mongoose?) comes to the court of Dharmarāja and says that his Aśvamedha is nothing compared to that of Ucchavritti of Saktuprastha. Brāhmaṇa Ucchavritti was a resident of Kurukshetra (सक्तुप्रस्थेन वो नायं यज्ञस्तुल्यो नराधिप । उच्चवृत्तेर्वदान्यस्य कुरुक्षेत्रनिवासिनः ॥). - According to Tamil legends of the Sangam era, Alli Arasani was the only child of the Pāndya king. She learnt Yuddhavidyā in a Gurukula. Once Neenmughan (Nilamukha) usurped Pāndyan Kingdom but Alli Arasani led the Pāndyan army and killed Neenmughan. Thus, she succeeded her father and became the queen of Then Madurai (ancient Madurai that was submerged by the sea). She reigned over the Pāndya Kingdom, extended up to Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka was well connected through land route and Tāmraparṇi River of the Pāndya Kingdom used to flow into Sri Lanka before 7000 BCE. Arjuna came to Madurai following the Aśvamedha horse. He wanted to marry Alli Arasani but she sent the Nāgas to kill him. Arjuna somehow entered the palace of Alli Arasani in the guise of a Nāga and slept with her. He also tied Tāli on her. Finally, Arjuna succeeded in marrying Alli Arasani. Alli Arasani was also considered to be an incarnation of Mīnākśī.

- Jaiminiya Aśvamedha also relates the story of Nala and Damayanti and Kuśa and Lava, the sons of Rāma. Evidently, the available text of Jaiminīya Aśvamedha was written after the Rāmāyaṇa era.

- The story of Jaiminīya Aśvamedha indicates that Dharmarāja, Bhima, Arjuna (Phalguna), Sri Krishna Vriṣadhvaja and Meghavarṇa were all contemporaries of the Ikśvāku king Māndhātā and his son Muchukunda. Māndhātā had performed 100 Aśvamedhas. Therefore, Māndhātā had a suitable horse for Aśvamedha. Arjuna met Rishi Saubhari who was a junior contemporary of Māndhātā. Arjuna also met Vaka Dālbhya who was a contemporary of the Nāga king Dhritarāṣṭra Vaichitravīrya as mentioned in Kāthaka Saṁhitā. Durbuddhi, son of Dhritarāṣṭra, went to Maṇipura to kill Arjuna. Evidently, the story of Jaiminīya Aśvamedha belonged to the Rigvedic era. Unfortunately, the stories of Jaiminīya Aśvamedha and Vyāsa’s Mahābhārata got mixed up and led to numerous chronological inconsistencies.

- Vyāsa’s Mahābhārata clearly tells us that Arjuna of the Mahābhārata era went northwards and conquered up to Uttara Kuru, during the Rājasūya Yajña of Yudhiṣṭhira. He never went to South India. Moreover, almost all kings and armies of entire India participated in the Mahābhārata War. Yudhiṣṭhira became the emperor of a vast kingdom after the Mahābhārata War. It is unimaginable that Yudhiṣṭhira had performed Aśvamedha and sent Sri Krishna and Arjuna to conquer entire India after the Mahābhārata War. There was absolutely no need to perform Aśvamedha because he was already ruling over a vast kingdom and no other king had resources and energy to challenge Yudhiṣṭhira after the Mahābhārata War. It took more than sixteen years to overcome the pain of the Mahābhārata War for Dhritarāṣṭra, Gāndhārī, and Kunti. No sensible king would even think of waging another war after the gruesome battle of the Mahābhārata. My research reveals that Yudhiṣṭhira of the Mahābhārata era did not perform Aśvamedha. In fact, Dharmarāja of the Rigvedic era performed Aśvamedha. Later Puranic updaters added Aśvamedha Parva (14th), Svargārohaṇa Parva (18th) and more to Vyāsa’s Mahābhārata because they have erroneously mixed up the stories of Jaiminīya Aśvamedha and Vyāsa’s Mahābhārata.

- Puranic updaters also mistakenly considered Yudhiṣṭhira of the Mahābhārata era and Dharmarāja of the Rigvedic era as identical. Dharmarāja of the Rigvedic era was a son of Yama Dharmarāja.

- Rishi Uttaṅka was the contemporary of three generations of Ikśvāku kings Kuvalayāśva, Yuvanāśva and Yauvanāśva (Māndhātā). Rishi Uttaṅka also met Devakīputra Krishna. I have already explained that Devakīputra Krishna lived in the Rigvedic era and Krishna of the Mahābhārata era lived around 3223-3126 BCE.

- Ghaṭotkacha was the son of Bhima and Hiḍimbi. He married Ahilawati, also known as Maurvi, daughter of King Muru of the Yadu dynasty, and had three sons, Barbarīka, Añjanaparvan and Meghavarṇa. Irāvān was the son of Arjuna and Nāga princess Ulūpi. In all probability, Hiḍimba, Hidimbī and Ghaṭotkacha belonged to subspecies of Homo sapiens called “Cro-Magnon Man” that became extinct around 10000 BCE. Meghavarṇa, son of Ghaṭotkacha, lived around 11100 BCE when Dharmarāja of Hastinapura performed Aśvamedha Yajña.

It is evident that Devakīputra Vāsudeva Krishna lived in the Rigvedic era around 11150-11050 BCE and was the pupil of Ghora Āṅgirasa, whereas Sri Krishna, a descendant of Vāsudeva Krishna, lived in the Mahābhārata era around 3223-3126 BCE.

The Date of the submergence of Dvāravatī (Dwarka)

Modern historians have concluded that the references of the lost city of Dvāravatī or Dwarka in Indian literature and the references of the lost city of Atlantis in Greek literature are mythical. But the new researches in Indian and world chronology clearly indicate that the civilizational history of the ancient nations of the world arguably commenced at the beginning of Holocene.

Devakīputra Krishna founded the city of Dvāravatī and Viśvakarmā was the civil engineer who planned the city. Dvāravatī city was built on the same place where the city of Kuśasthalī existed. Kuśasthalī was the earliest capital of Saurashtra. King Raivata Manu (12500 BCE) founded this city near Raivataka Hill, or Girnar. Harivaṁśa Purāṇa relates that Sri Krishna built the city of Dvāravatī on the land released by the ocean. Probably, Kushasthali was submerged by the sea during Meltwater Pulse 1A, around 12000-11800 BCE, but resurfaced later.

According to Harivaṁśa, Dvāravatī was located close to the Girnar (Raivataka) Hill (बभौ रैवतकः शैलो रम्यसानुगुहाजिरः). A river was also flowing into the city (महानदी द्वारवतीं पञ्चाशद्भिर्महामुखैः, प्रविष्टा पुण्यसलिला भावयन्ती समन्ततः). The length of Dvāravatī city was twelve Yojanas and the breadth was eight Yojanas (अष्टयोजनविस्तीर्णामचलां द्वादशायताम्, द्विगुणोपनिवेशां च ददर्श द्वारकां पुरीम्). It may be noted that Yojana was equal to 165-169m during the Vedic, post-Vedic and Rāmāyaṇa eras. Later, Yojana became equal to 13 km during the Mahābhārata era. Thus, Dwārakā city had a length of 2 km and the breadth of 1.5 km.

When Devakīputra Krishna died, succumbing to the arrow of a hunter around 11000 BCE, Dravida, son of Jāmbavatī, might have succeeded him in Dwārakā because Jāmbavatī’s elder son Sāmba was cursed with leprosy by Sri Krishna. Sāmba had to do penance for twelve years. Pradyumna was killed in Dwārakā and his son Aniruddha ruled in Mathura. Seemingly, Dravida, son of Jāmbavatī, became the King of Dwārakā after the death of Pradyumna. Tamil poet Kapilar of the Sangam era clearly mentions in his poems (Stanza 201 and 202 of Purāṇanuru) that the ancestors of Velir King Irunkovel were the rulers of the fortified city of “Tuvarai”. Nacchinarkkiniyar, a commentator of “Tolkappiyam”, records the migration of the Velir kings from the city of “Tuvarai” or “Tuvarāpati” to Tamil Nadu. He indicates that the Velirs came to Tamil Nadu under the leadership of Rishi Akattiyanar (i.e. Agastya) and they belonged to the lineage of Netumutiyannal (i.e. Krishna). A Tamil inscription (Pudukottai State Inscriptions No. 120) also mentions the migration of the Velir kings from the city of “Tuvarai”. Undoubtedly, “Tuvarai” or “Tuvarāpati” was the city of Dvāravatī or Dwārakā founded by Devakīputra Krishna.

Interestingly, the inscription of Velir king Satyaputra Athiyaman Neduman Anchi is found on the hillock named Jambaimalai of Jambai village in Villuppuram district of Tamil Nadu. It is generally argued that the village got its name from the Jambunatheshvar temple but this Śiva temple itself is named after Jambunath. Evidently, Jambunath was none other than Jāmbavān, the father of Jāmbavatī. Since the Velir or Satyaputra kings were the progeny of Jāmbavatī, the Śiva Temple of Jambai village was named after Jambunath or Jāmbavān. Thus, we can conclusively establish that the ancestors of the Velir kings had migrated from the city of Dvāravatī and they were the progeny of Devakīputra Krishna and Jāmbavatī.

Bhāgavata Purāṇa relates that Devakīputra Krishna married Jāmbavatī, daughter of King Jāmbavān. Jāmbavatī was the mother of Sāmba, Sumitra, Purujit, Śatajit, Sahasrajit, Vijaya, Chitraketu, Vasuman, Dravida and Kratu. Thus, Dravida was the son of Krishna I and Jāmbavatī. These Velir kings, or the descendants of Dravida, migrated to South India and established their kingdom in the region between Tondaimandalam and the Chola Kingdom. Manusmriti mentions that the Dravidas were the Vrātya Kśatriyas because Jāmbavatī, mother of Dravida, was probably a non-Kśatriya princess.

According to Kapilar, forty-eight generations or forty-eight ancestors of ancient Irunko kings or ancient Velir kings reigned at Dvāravatī. He mentioned the title of “Settirunko” which means “Jyeṣṭha Irunko” or Irunkovel I. There were many Velir kings who had the title of “Irunkovel”. Some Tamil inscriptions refer to the Velir kings as Irunko Muttaraisar, i.e., ancient Irunko kings. Therefore, Kapilar refers to the first Irunkovel as “Settirunko”. Most probably, Irunkovel I was the forty-ninth Velir king who reigned at Dvāravatī.

Seemingly, forty-nine descendants of King Dravida reigned at Dvāravatī approximately for 1650 years, from 11050 BCE to 9400 BCE, considering the average reign of 33 years for each king. Dvāravatī was submerged by the sea around 9400-9300 BCE, during the reign of Irunkovel I, the forty-ninth king.

According to oceanographic studies, sea level suddenly rose 28m in 500 years, about 10000-9500 years ago. This accelerated sea level of 10000-9400 BCE has been named Meltwater Pulse 1B. Many Yādava families had to migrate eastwards and southwards. It appears that Indian astronomers observed the event of “Rohiṇī Śakaṭa Bheda” (when either Mars or Saturn pass through Rohiṇī Śakaṭa, i.e. the triangle formation of stars in Taurus constellation) several times around 9400-9300 BCE. Probably, Dvāravatī city was submerged by the sea around 9400-9300 BCE. This may be the reason why Rishi Gārga’s astrology had correlated Rohiṇī Śakaṭa Bheda with a deadly disaster. Lāṭadeva (3160-3080 BCE) also refers to Rohiṇī Śakata Bheda in his Sūrya Siddhānta because Saturn occulted e-Tauri during the Mahābhārata era.

The Sunken City of Atlantis

Greek philosopher Plato narrates the story of the city of Atlantis. According to him, the residents of Atlantis Island were seafaring people. Most probably, these seafaring people were the Paṇi Asuras who migrated from India (Gāndhāra) after 11000 BCE, due to weakening of monsoons. These Paṇis dominated in the region of the Mediterranean Sea. Plato says that the Atlantis people had conquered parts of Libya, Egypt among others and enslaved the people. The people of Athens fought against the invaders of Atlantis and conquered back parts of Libya and Egypt. He states that the Island city of Atlantis was located beyond the Pillars of Hercules at the strait of Gibraltar.

Interestingly, Plato states that the city of Atlantis was also submerged by the sea 9000 years before his lifetime. Modern historians date Plato around 428-348 BCE but considering the error of 660 years in the chronology of world history, Plato lived around 1088-1008 BCE.9 Thus, the city of Atlantis might have been submerged by the sea around 10000 BCE. Evidently, the cities of Dvāravatī and Atlantis were submerged by the sea during the beginning of the accelerated rise of sea level, i.e. Meltwater Pulse 1B, around 10000 BCE.

Most probably, the descendants of Danu (Dānavas) migrated to Anatolia and Greece around 12000-11000 BCE and settled at Athens. Asuras migrated to Syria and came to be known as Assyrians. The Paṇis migrated to Lebanon, Cyprus and suchlike, and came to be known as Phoenicians. Druhyu’s sons migrated to Syria and came to be known as Druze. The Asuras of Airyāna region (ancient Iran) came to be known as Airans. Modern linguists have misinterpreted Airans as Aryans.

The Identification of the ancient city of Dvāravatī

Puranic legends relate that Devakīputra Krishna shifted his capital from Mathura to Dvāravatī after the killing of Kamsa. The invasions of Jarāsandha I and Kālayavana also compelled Krishna to move to Dvāravatī (कृष्णोऽपि कालयवनं ज्ञात्वा केशिनिषूदनः । जरासंधभयाच्चैव पुरीं द्वारवतीं ययौ ॥)10 According to Harivaṁśa, Sri Krishna selected the area of ancient city of Kuśasthalī that was reclaimed from sea and requested Viśvakarmā to plan and design the entire city (देव यास्यामि नगरीं रैवतस्य कुशस्थलीम् । , वासार्थमीक्षितुं भूमिं तव देव कुशस्थलीम् ।, तस्मिन्नेव ततः काले शिल्पाचार्यो महामतिः । विश्वकर्मा सुरश्रेष्ठः कृष्णस्य प्रमुखे स्थितः ॥).

Raivata Manu (12500 BCE) built the city of Kuśasthalī. This city was submerged by the sea during the period of Meltwater Pulse 1A, around 12000 BCE. Raivata Manu’s descendants had to shift their capital from Kuśasthalī to Prabhas Pātan-Kodinar region. King Kakuda or Kakudmi, the last known descendant of Raivata Manu, was the ruler of the region of Raivataka Hills or Saurashtra (किमर्थं च परित्यज्य मथुरां मधुसूदनः । मध्यदेशस्य ककुदं धाम लक्ष्म्याश्च केवलम् ॥). His daughter Revatī was married to Baladeva, the elder brother of Devakīputra Krishna. Seemingly, the area of Kuśasthalī resurfaced from sea due to a massive earthquake around 11200 BCE. Devakīputra Krishna built the city of Dwārakā on the hillocks close to the sunken city of Kuśasthalī around 11100 BCE.

According to Harivaṁśa, Raivataka Hill (Girnar) was to the East of Dvāravatī, Pañchavarṇa in the South, Indraketu-Pratīkāśa (a hillock like Indraketu that was probably located on an island) in the West and Venumān Mandarādri-Pratīkāśa (a hill of Bamboo trees like Mandara Hill that was probably Barda Hill of Porbandar) in the North (वभौ रैवतकः शैलो रम्यसानुगुहाजिरः । पूर्वस्यां दिशि लक्ष्मीवान् मणिकाञ्चनतोरणः ॥ दक्षिणस्यां लतावेष्टः पञ्चवर्णो विराजते । इन्द्रकेतुप्रतीकाशः पश्चिमां दिशमाश्रितः ॥ सुकक्षो राजतः लश्चित्रपुष्पमहावनः ॥ उत्तरां दिशमत्यर्थं विभूषयति वेणुमान् । मन्दराद्रिप्रतीकाशः पाण्डुरः पार्थिवर्षभ ॥). A River named “Mahānadī” was also flowing through the city of Dvāravatī (महानदी द्वारवतीं पञ्चाशद्भिर्महामुखैः । प्रविष्टा पुण्यसलिला भावयन्ती समन्ततः ।।).

After the accidental death of Devakīputra Krishna, probably, Pradyumna, son of Krishna, ascended to the throne but he died at Dvāravatī in an internal conflict among Yādavas. Seemingly, Aniruddha, son of Pradyumna, had to move to Mathura. His son Vajra, or Vajranābha, succeeded him and became the King of Indraprastha. According to Tamil sources, forty-nine Velir kings or Dravida kings reigned at Dvāravatī. Dravidas or Velirs were the descendants of Dravida, son of Jāmbavatī. It appears that Dvāravatī started flooding at the end of Meltwater Pulse 1B, around 9400-9300 BCE (when the astronomical event of Rohiṇī Śakata Bheda was observed). Many Yādava families of Dvāravatī had to abandon the city built by Devakīputra Krishna. Some of them migrated to South India.

Puranic references unambiguously indicate the location of Dvāravatī close to Girnar Hills. Jain sources also acknowledge the presence of the city of Dvāravatī close to Girnar Hills. Recently, a submerged city in the Gulf of Khambat has been discovered in 2001. Khambat area was known as Sthaṁbhatīrtha in ancient times (तत्कृत्वा सानुमान्यैतान्स्तंभतीर्थमुपागता).16 Marine archaeologists found a piece of wood in this submerged city and it was carbon dated to 7545-7490 BCE. Undoubtedly, this sunken city in the Gulf of Khambat was the original Dvāravatī, or Dwārakā, founded by Sri Krishna. Most probably, Dvāravatī city was flooded by the sea around 9400-9300 BCE, at the end of Meltwater Pulse 1B. Seemingly, it took at least 1500 years to completely submerge the area of Dvāravatī city. Thus, the piece of wood found in the area of the sunken city in the Gulf of Khambat was submerged around 8000-7500 BCE.

It is well known that the sea level of Gujarat coast was 100m below before the event of MWP 1A (12000 BCE). Though the low areas of Dvāravatī flooded around 9400-9300 BCE, it gradually submerged during the period 9400-7500 BCE. The sea level remained almost unchanged for 2000 years around 9500-7500 BCE. This may be the reason why a piece of wood is carbon dated around 7500 BCE.

Sh. Badrinarayan of NIOT (National Institute of Ocean Technology) studied the sunken city that was found 40m deep and 20 km away from the shores, in the Gulf of Khambat. A fortress found underwater is nearly 98m in length. The findings of the research on this sunken city are as under:

The research on the two sunken townships in the Gulf of Khambat reveals that the southern township was gradually submerged around 9400-7500 BCE and the northern township was submerged around 1500-1000 BCE. Evidently, the southern township was the ancient city of Kuśasthalī and Dvāravatī. This area had the presence of humans since 30000 BCE. Raivata Manu built the city of Kuśashthalī around 12500 BCE, which was submerged around 12000 BCE. Most probably, the area of Kuśasthalī and the area of Śūrpāraka (near Sopara, a town in Thana district) resurfaced in a massive earthquake around 11200 BCE. The Puranic legends relate that Paraśurāma (11220-11120 BCE) reclaimed the area of Śūrpāraka and Devakīputra Krishna (11150-11050 BCE) reclaimed the area of Kuśasthalī from the sea. The same earthquake might have opened up the Baramulla Pass, which resulted in a heavy outflow of water from the glacial lake of Kashmir valley. This also led to a massive flood in Sindh and Gujarat, which is nothing but the legend of the great flood during the time of Vaivasvata Manu. Seemingly, this massive earthquake caused tsunamis that were mythologized as Samudra Manthana.

Devakīputra Krishna built the city of Dvāravatī around 11100 BCE on the reclaimed land of the city of Kuśasthalī and it was submerged around 9400-9300 BCE. This sunken city of Dvāravatī was indeed the southern township found in the Gulf of Khambat. In all probability, the Yādavas of Dvāravatī city might have built the northern township of Dvāravatī (second city of Dwārakā) after the submergence of southern township. Possibly, this northern township (second Dwārakā) existed during the Mahābhārata era (3162 BCE), which was suddenly flooded in a tsunami. This northern township was completely submerged by the sea around 2000-1500 BCE.

Some scholars identified Bet Dwārakā as the city of Dwārakā of the Mahābhārata era. First of all, none of the literary or traditional sources indicate the location of Dwārakā in the Gulf of Kutch. Moreover, Bet Dwārakā was known as the Shankhoddhar Tirth because Sri Krishna killed Śaṅkhāsura in this region. Therefore, Bet Dwārakā cannot be identified as the city of Dvāravatī built by Devakīputra Krishna.

Jaiminīya Aśvamedha and Vyāsa’s Mahābhārata

According to a legend, Vyāsa’s five disciples composed their versions of the Mahābhārata but Vyāsa rejected all of them. Another legend says that Jaimini wrote his version of the Mahābhārata. A Marathi text Pāndavapratāpa, written by Shridhara (17th century), mentions that Vyāsa condemned Jaimini for composing his version of the Mahābhārata but only Aśvamedha Parva of Jaiminīya Mahābhārata is extant today, because Jaimini had recited it to Janamejaya. Seemingly, these legends are mere speculations by later authors. There is no such information available in ancient texts.

Probably, an Itihasa text on Aśvamedha was composed in the post-Vedic era. Since Jaimini narrated the story of Aśvamedha to Kuru King Janamejaya of the Vedic period, it came to be known as Jaiminīya Aśvamedha. There is a dialogue between Jaimini and Mārkanḍeya in Mārkanḍeya Purāṇa. There were many Vyāsas and Jaiminis. It is difficult to establish the authorship of Jaiminīya Aśvamedha but it is certainly an ancient Itihasa text. The text was probably recompiled in ślokas after the Rāmāyaṇa era and certain chapters like Nalopākhyāna, Kuśa-Lavopākhyāna, Sahasramukharāvaṇachritam (Sitāvijayam) and Mairāvaṇacharitam had been added. During the period 1500-1000 BCE, Jaiminiya Aśvamedha has been again recompiled along with other Itihasa and Purāṇa texts. The famous “Anugītā”, with thirty-six chapters, is part of Jaiminīya Aśvamedha (Chapter 16 to Chapter 51). Ādi Śaṅkara (568-536 BCE) quoted Anugītā in his commentary on Bhagavad Gitā. Evidently, Jaiminīya Aśvamedha was a popular Itihasa text since ancient times. Interestingly, Jaiminīya Aśvamedha was also translated along with the Mahābhārata into Persian (named Razmnama) during the time of Akbar.

The later updaters of Jaiminīya Aśvamedha had mistakenly assumed Veda Vyāsa and Devakīputra Krishna to be identical with Vyāsa and Krishna of the Mahābhārata era respectively. This chronological error led to a speculative theory that Jaimini also wrote the Mahābhārata, but only Aśvamedha Parva was survived. In reality, Jaiminīya Aśvamedha relates the story of Aśvamedha performed in the Rigvedic era, whereas the Mahābhārata relates the history of the 32nd century BCE. Lakshmisha wrote “Jaimini Bhārata” in Kannada, based on Jaiminīya Aśvamedha. Therefore, Lakshmisha’s Jaimini Bhārata differs from Kumara Vyāsa’s (Narayanappa’s) Karṇāta Bhārata Kathāmañjarī. The story of Kirātārjunīyam, the historical site of Arjuna’s penance, and the descent of Ganga River by Bhagīratha (Mahabalipuram), indicate the popularity of Arjuna of Vedic times. Arjuna of the Rigvedic era was known as Phalguna. Evidently, Jaiminīya Aśvamedha was popular since ancient times. Let us chronologically analyze the historical events narrated in Jaiminīya Aśvamedha:

Evidently, the historical events narrated in Jaiminīya Aśvamedha took place in the Rigvedic era, around 11100 BCE, whereas the Mahābhārata war occurred in 3162 BCE. We can also resolve many chronological inconsistencies in historical legends. According to the Mahābhārata, Paraśurama (11220-11120 BCE), a contemporary of Kārtavīryārjuna, was the teacher of Bhishma, Droṇa and Karṇa. Hanuman I (11200-11100 BCE), son of Añjanā and Vāyu, was a contemporary of Bhima of the Jaiminīya Aśvamedha era, whereas Hanuman II lived in the Rāmāyaṇa era. Jāmbavān II (11160-11080 BCE) was a senior contemporary of Devakīputra Krishna, whereas Jāmbavān III lived in the Rāmāyaṇa era.